External Web Site Notice: This page contains information directly presented from an external source. The terms and conditions of this page may not be the same as those of this website. Click here to read the full disclaimer notice for external websites. Thank you.

History

"The events of 1914 through 1918 shaped the world,

the United States, and the lives of millions of people."

from The World War One Centennial Commission Act, January 14, 2013

World War One Education Resources

"The centennial of World War One offers an opportunity for people in the United States

to learn about and commemorate the sacrifices of their predecessors."

from The World War One Centennial Commission Act, January 14, 2013

Commemorating The Great War

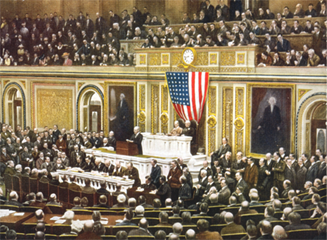

"The world must be made safe for democracy. Its peace must be planted upon the tested foundations of political liberty. We have no selfish ends to serve. We desire no conquest, no dominion. We seek no indemnities for ourselves, no material compensation for the sacrifices we shall freely make. We are but one of the champions of the rights of mankind. We shall be satisfied when those rights have been made as secure as the faith and the freedom of nations can make them.... It is a fearful thing to lead this great peaceful people into war, into the most terrible and disastrous of all wars, civilization itself seeming to be in the balance. But the right is more precious than peace, and we shall fight for the things which we have always carried nearest our hearts—for democracy, for the right of those who submit to authority to have a voice in their own governments, for the rights and liberties of small nations, for a universal dominion of right by such a concert of free peoples as shall bring peace and safety to all nations and make the world itself at last free."

President Woodrow Wilson

Address to Congress, 2 April 1917

100 Years Ago

World War One—called the "Great War" until the world learned that there would be more than one such war in the twentieth century—was the first total war of the modern period. The participants, unprepared for the long and bloody conflict that ensued after the summer of 1914, scrambled to mobilize their manpower and industry to prosecute the war. All searched for a decisive military victory. Instead, dramatic and largely unforeseen changes in warfare quickly followed one another, in the end altering both Europe and the larger Western culture that it represented. Although the bloody conflict finally ended with an armistice in November 1918, it cast a long politico-military shadow over the decades that followed.

T he United States reluctantly entered Europe's "Great War" and tipped the balance to Allied victory. In part the nation was responding to threats to its own economic and diplomatic interests. But it also wanted, in the words of President Woodrow Wilson, to "make the world safe for democracy." The United States emerged from the war a significant, but reluctant, world power.

he United States reluctantly entered Europe's "Great War" and tipped the balance to Allied victory. In part the nation was responding to threats to its own economic and diplomatic interests. But it also wanted, in the words of President Woodrow Wilson, to "make the world safe for democracy." The United States emerged from the war a significant, but reluctant, world power.

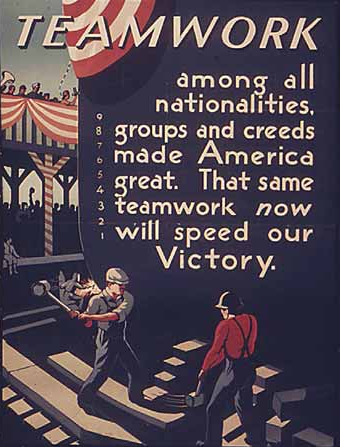

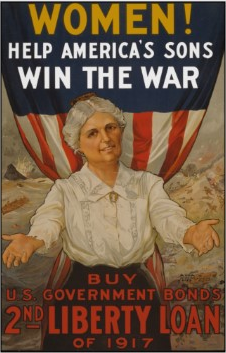

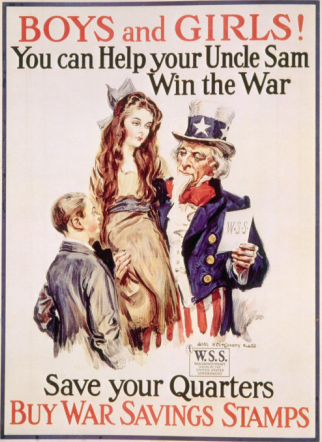

Under unprecedented government direction, American industry mobilized to produce weapons, equipment, munitions, and supplies. Nearly one million women joined the workforce. Hundreds of thousands of African Americans from the South migrated north to work in factories.

Two million Americans volunteered for the army, and nearly three million were drafted. More than 350,000 African Americans served, in segregated units. For the first time, women were in the ranks, nearly 13,000 in the navy as Yeoman (F) (for female) and in the marines. More than 20,000 women served in the Army and Navy Nurse Corps.  The first contingent of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF), commanded by General John J. Pershing reached France in June, but it took time to assemble, train, and equip a fighting force. By spring 1918, the AEF was ready, first blunting a German offensive at Belleau Wood.

The first contingent of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF), commanded by General John J. Pershing reached France in June, but it took time to assemble, train, and equip a fighting force. By spring 1918, the AEF was ready, first blunting a German offensive at Belleau Wood.

The Americans entered a war that was deadlocked. Opposing armies were dug in, facing each other in trenches that ran nearly 500 miles across northern France—the notorious western front.  Almost three years of horrific fighting resulted in huge losses, but no discernable advantage for either side. American involvement in the war was decisive. Within eighteen months, the sheer number of American "doughboys" added to the lines ended more than three years of stalemate. Germany agreed to an armistice on November 11, 1918.

Almost three years of horrific fighting resulted in huge losses, but no discernable advantage for either side. American involvement in the war was decisive. Within eighteen months, the sheer number of American "doughboys" added to the lines ended more than three years of stalemate. Germany agreed to an armistice on November 11, 1918.

Two million men in the American Expeditionary Force went to France. Some 1,261 combat veterans—and their commander, General Pershing—were awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, the nation's second-highest award for extraordinary heroism. Sixty-nine American civilians also received the award.

To learn even more about the Great War, click on the "History" button at the top of the page.

The Commemoration

From 2017 through 2019, the World War One Centennial Commission will coordinate events and activities commemorating the Centennial of the Great War. (Why?) The Commission has partnered with a broad range of organizations across the United States and around the world to spotlight events publications, productions, activities, programs, and sites that allow people in the United States to learn about the history of World War One, the United States involvement in that war, and the war's effects on the remainder of the 20th century, and to commemorate and honor the participation of the United States and its citizens in the war effort.

The Commission will serve as a clearing house for the collection and dissemination of information about events and plans for the centennial of World War One. The Commission will also encourage private organizations and State and local governments to organize and participate in activities commemorating the centennial of World War One.