The Star-Spangled Banner and World War One

During the War of 1812, Francis Scott Key and the American Prisoner Exchange Agent Colonel John Stuart Skinner dined aboard the British ship HMS Tonnant, as the guests of three British officers: Vice Admiral Alexander Cochrane, Rear Admiral Sir George Cockburn, and Major General Robert Ross.

During the War of 1812, Francis Scott Key and the American Prisoner Exchange Agent Colonel John Stuart Skinner dined aboard the British ship HMS Tonnant, as the guests of three British officers: Vice Admiral Alexander Cochrane, Rear Admiral Sir George Cockburn, and Major General Robert Ross.

Skinner and Key were there to negotiate the release of prisoners, one being Dr. William Beanes. Beanes was a resident of Upper Marlboro, Maryland and had been captured by the British after he placed rowdy stragglers under citizen's arrest with a group of men.

Skinner and Key were there to negotiate the release of prisoners, one being Dr. William Beanes. Beanes was a resident of Upper Marlboro, Maryland and had been captured by the British after he placed rowdy stragglers under citizen's arrest with a group of men.

Skinner, Key, and Beanes were not allowed to return to their own sloop: they had become familiar with the strength and position of the British units and with the British intent to attack Baltimore.

As a result of this, Key was unable to do anything but watch the bombarding of the American forces at Fort McHenry during the Battle of Baltimore on the night of September 13 – September 14, 1814.

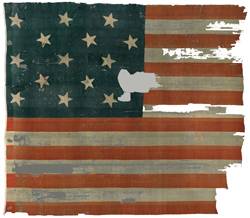

At dawn, Key was able to see an American flag still waving and reported this to the prisoners below deck. On the way back to Baltimore, he was inspired to write a poem describing his experience, "Defence of Fort McHenry", which he published in the Patriot on September 20, 1814. He intended to fit it to the rhythms of composer John Stafford Smith's "To Anacreon in Heaven", a popular tune Key had already used as the setting for his 1805 song "When the Warrior Returns," celebrating U.S. heroes of the First Barbary War. The earlier song is also Key's original use of the "star spangled" flag imagery.

The song has since become better known as "The Star Spangled Banner". Under this name, the song was adopted as the American national anthem, first by an Executive Order from President Woodrow Wilson in 1916, which had little effect beyond requiring military bands to play the War Department standard arrangement to be used by U.S. military bands. But it was not until the 1918 World Series that the song took hold of America during a game that almost didn’t happen.

The song has since become better known as "The Star Spangled Banner". Under this name, the song was adopted as the American national anthem, first by an Executive Order from President Woodrow Wilson in 1916, which had little effect beyond requiring military bands to play the War Department standard arrangement to be used by U.S. military bands. But it was not until the 1918 World Series that the song took hold of America during a game that almost didn’t happen.

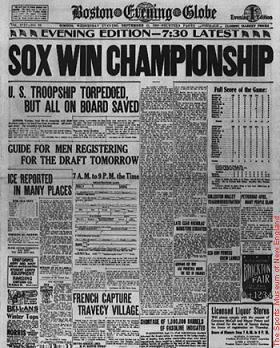

America had been involved in World War One for a year. Out of respect for the soldiers, baseball officials wanted to cancel the World Series between the Boston Red Sox and the Chicago Cubs. When it became known, however, that American soldiers fighting in France were eager to know the Series’ results, the games commenced. To honor these brave men, the officials had the band play the Star-Spangled Banner during the seventh-inning stretch of the first game. Comiskey Park in Chicago erupted in song as the spectators and players stood and joined in. Soon it became tradition to play the Star-Spangled Banner at all baseball games and, eventually, nearly all sporting events.

Prior to this World Series game, there had been a push to make the song our official anthem. The push gained momentum after the World Series as citizens and legislators worked tirelessly to make it happen. Finally, after twenty years and forty bills and resolutions, it became a reality. In 1931, President Herbert Hoover, our thirty-first president, elevated the song to the highest level. He signed a Congressional resolution in 1931 making the Star-Spangled Banner the national anthem.

The long journey from a poem written on the back of a letter to our country’s national anthem took 117 years.